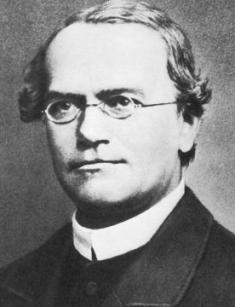

Gregor Mendel: biography

Gregor Mendel is a scientist and abbot known as the father of genetics. Although contemporaries did not appreciate his works, researchers of the early 20th century recognized him as the originator of all ideas in heredity studies.

Childhood and youth

There is little information about the biologist’s early years. He was born on July 20, 1822, in Hynčice, then Heinzendorf bei Odrau, Silesia, a part of the Austrian Empire.

The boy became the second child in the family of Anton and Rosine Mendel; he had two sisters, Veronica and Theresia. The family had German and Slavic roots and owned the land where they resided for more than a century. Today, the scientist’s childhood house is a museum.

Gregor showed an interest in nature early: he often gardened enthusiastically and kept bees. The boy was weak physically and had to miss classes because he was sick. When Mendel graduated from the village school, he entered a gymnasium in Opava and spent there six years.

The next three years, the young man got acquainted with practical and theoretical philosophy and physics at the Philosophical Institute of the University of Olomouc. Johann Karl Nestler chaired the faculty of Natural History and Agriculture at that time; the scientist researched genetically inherited traits in plants and animals, such as sheep.

Financial issues were depressing for Mendel. He could not pay for his education, and Theresia gave up her dowry so that her brother could continue to study. Later, Gregor returned all the money and helped his three nephews; two of them became doctors under his guidance.

In 1843, Mendel decided to go into a convent. Free education for the clergy rather than godliness determined this choice: according to Gregor, this life relieved him from permanent anxiety about bread and butter. As he took the religious vows at St. Thomas’ Abbey in Brno, Johann received the name “Gregor” and began to study at the Theological School and became a priest.

Science

A naturalist and religious man, Mendel became an ambiguous figure. His studies brought to existence the new discipline that described God’s design in terms of genes. Gregor’s thirst for knowledge was immense; he was devouring academic books and changed teachers in a local school when it was necessary. The man dreamed of passing the exam and becoming a teacher but failed his geology and biology tests.

In 1841-1851, Mendel taught languages and mathematics at the Znojmo gymnasium. Further on, he moved to Vienna and studied natural history at the University of Vienna until 1853. The botanist and one of the first cytologists Franz Unger was his mentor; besides, the famous physicist Christian Doppler taught him physics.

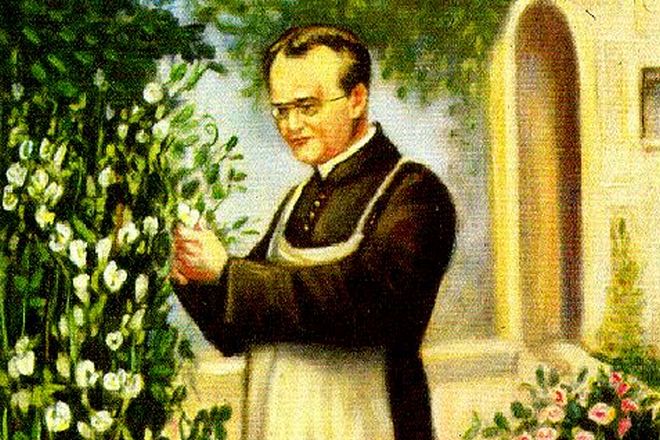

As soon as the scientist came back to Brünn, he taught the same subjects at high school, even though he had no diploma. In 1856, Mendel had another attempt to pass the exams but failed biology again. The same year brought interest in scientific experiments with plants and crossbreeding. For the next seven years, until 1863, Gregor experimented with peas in a monastery garden and made his wonderful discoveries.

Although plant hybridization had begun long before Mendel, only the scientist managed to find consistent patterns and formulate the main points that genetics used until the 1970s. Gregor conducted more than 10 000 experiments twenty-something species of peas; all of them had different flowers and seeds. It was a colossal amount of work: each pea was examined thoroughly. To investigate only one trait, shape (round-wrinkled), Gregor checked more than 7000 peas; there were seven traits in his work.

The fundament of genetics, the teachings on heredity, were formed thanks to these experiments. In 1865, Mendel published Experiments on Plant Hybridization in the journal Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn. He formulated the main regularities of heredity known as Mendelian inheritance.

The scientist’s ideas are as follows:

- First-generation hybrids are the same and bear a dominant of one parent. For instance, if peas with white and red flowers are crossed, the offspring will have only red flowers.

- Second-generation hybrids split: some of them receive a parent’s dominants while others receive recessive traits. The assortment is expressed mathematically.

- Both traits exist in various combinations and do that independently. Hybrids that seem to have dominant traits may have recessive genes and vice versa; these traits will manifest themselves in new generations.

- Malу and female gametes pair accidentally, with no relation to their properties.

Gregor was sure that his research was fundamental and had dozens of copies ordered to send to famous botanists of the epoch. Unfortunately, contemporaries were not interested in the publication. Only the professor of the Munich University Carl von Nägeli recommended his colleague to test the theory on other species.

Mendel conducted a series of experiments on other plants and insects – his favorite bees. It turned out that both of them had peculiarities of the insemination process and could reproduce by parthenogenesis, or the virginal generation. As a result, the data from the first experiment was not proven.

In 1900, several independent scientists came to the same ideas as Mendel introduced. It was the birth of the new science, genetics; Mendel’s contribution to it was substantial.

Religion

Mendel took the religious vows at 21; material issues and access to knowledge were the primary reasons. This way implied personal limits, and he never married or had children, according to the Catholic tradition.

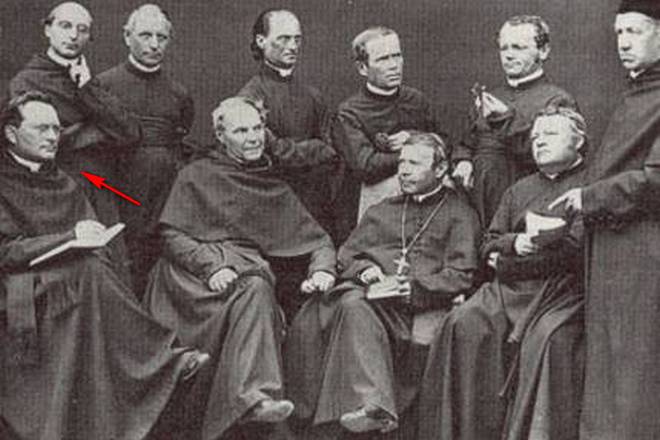

At 25, the young man became a priest at the Augustinian St. Thomas’s Abbey, the cultural and scientific center in the region. Abbot Napp encouraged his monks’ interest in science; the brethren supervised children’s education. Mendel eagerly taught kids, and they loved him.

In 1868, after Napp’s death, Gregor took his position and finished his big scientific activities, for it was necessary to take care of the holy place. Mendel did the administration work and opposed the secular authorities that were going to introduce additional taxes for religious institutes. He continued to hold the office until his last days.

Death

61-year-old Abbot Mendel died in 1884; chronic nephritis was the cause of death. He served to the abbey for almost 40 years, and the scientist’s museum was opened there later.

Mendel was buried in Brno. Onу can read on his monument:

“My time will come” – the researcher used to say it in his lifetime.

Bibliography

- 1866 - Experiments on Plant Hybridization