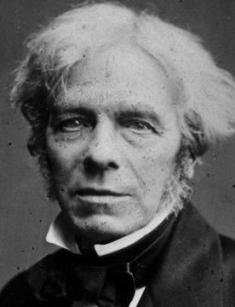

Michael Faraday: biography

Michael Faraday is an English experimental physicist and chemist who researched electromagnetic field and discovered electromagnetic induction, the fundament of the present-day electricity production.

Childhood and youth

The future scientist was born on September 22, 1791, in Newington Butts, not far from London. The boy’s father, James, was a blacksmith; the mother’s name was Margaret. Michael had three siblings: the brother Robert and the sisters Elizabeth and Margaret.

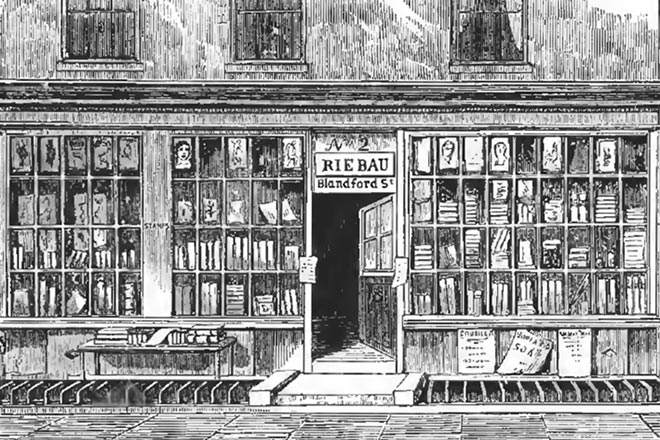

The family was not wealthy, and Michael had no chance to graduate from school; he had to become an errand boy at a bookstore at the age of 13. However, books on chemistry and physics quenched the thirst for knowledge. Young Michael created a current source, a Leyden jar. The father and brother supported his urge to experiment.

In 1810, the 19-year-old young man joined a philosophical club and attended lectures on physics and astronomy there, participating in academic discussions. Soon, the scientific community noticed Faradays’ talent. A bookstore customer, William Dance, gave him a ticket for lectures on chemistry and physics as a present, and Michael could listen to Humphry Davy, the founder of electrochemistry who discovered Potassium, Calcium, Sodium, Barium, and Boron.

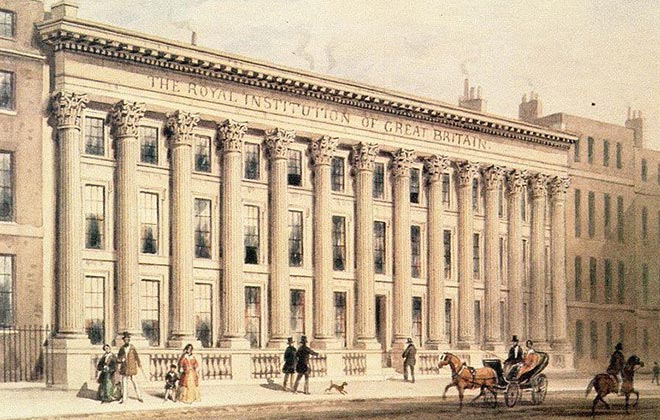

The would-be researched wrote Davy’s lectures in shorthand, bounded it, and sent it to the professor with a request letter: Faraday hoped the scientist would have some job for him at the Royal Institution. Davy helped the young man, and 22-year-old Michael became an assistant at a chemical laboratory.

Science

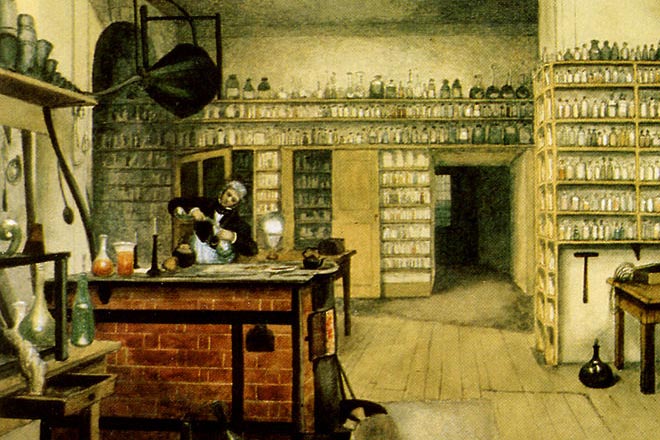

Faraday performed his duties and listened to the lectures he had helped to prepare. Besides, he conducted his own experiments in chemistry with the professor’s permission. The young man worked carefully and skillfully; his traits made him Davy’s irreplaceable associate.

In 1813, the scientist took Faraday as his secretary at a two-year journey in Europe. Michael had the opportunity to meet many top researchers: André-Marie Ampère, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, Alessandro Volta. In 1815, he returned to London and became an assistant, continuing his favorite activity – experiments. All in all, Faraday conducted more than 30 000 experiments throughout his life; colleagues called him the king of experimentalists for his industriousness and pedantry. The researcher described every attempt in his diaries; these notes were published in 1931.

Faraday’s first publication came out in 1816. By 1819, 40 works on chemistry had been released. In 1820, the young scientist experimented with alloys and discovered that steel with nickel did not give corrosion. However, this achievement passed unnoticed; stainless steel was patented later.

In 1820, Faraday became the technical inspector at the Royal Institute. The next year, the researcher’s interest shifted from chemistry to physics. Faraday earned respect from scientists and published the article on the principles of an electro engine work; it marked the beginning of the industrial electric engineering.

Electromagnetic field

Faraday took an interest in the interaction between electricity and magnetic field in 1820, when the terms “constant current source” (Alessandro Volta), “electrolysis”, “voltaic arc”, and “electric magnet” had appeared. Electrostatics and electrodynamics were developing, and Biot, Savart, and Laplace presented the results of their experiments on electricity and magnetism. Besides, Ampère’s work on electromagnetism had been published.

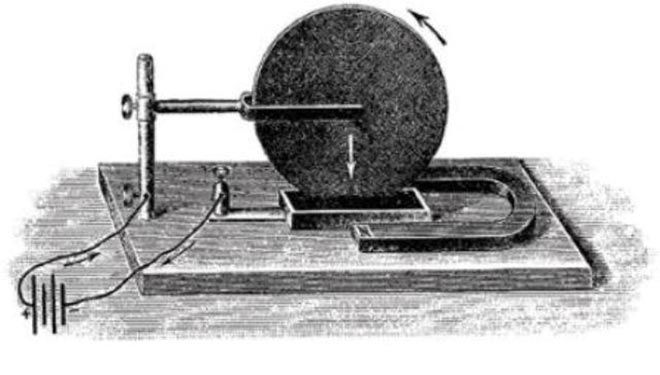

In 1821, Faraday’s On Some New Electro-Magnetical Motions, and on the Theory of Magnetism was released. The scientist presented the experiment with a magnetic needle spinning around a pole – he actually transformed the electric energy into the mechanic one. It was the first primitive engine working on electricity.

The joy of discovery was darkened by William Hyde Wollaston’s complain: he accused Faraday of stealing the idea and told Professor Davy about it. The scandal erupted. Davy took Wollaston’s side, and only the meeting of two scientists and Faradays’ explanations made the things clear. Eventually, Wollaston left his accusations, but the trust between Davy and Faraday was never strong from that moment, even though the former always said that Michael was his most significant discovery.

In 1823, Faraday became a corresponding member of Academy Science, France. The next year, in January, Faraday was elected a member of the Royal Society; Davy voted against it.

In 1825, Michael replaced his mentor and took the position of the Director of the Laboratory of the Royal Institution. Following the discovery in 1821, the scientist did not release any publication for ten years. In 1831, he became the professor at Woolwich’s military academy; the position of the Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution followed in 1833. Michael conducted scientific disputes and delivered lectures at scientific meetings.

In 1820, Faraday took an interest in Hans Christian Ørsted’s experiment: a magnetic needle moved when a current was moving in a circuit, and the current caused magnetism. Faraday assumed that magnetism could originate a current; this theory was first mentioned in the man’s diary in 1822. It took him ten years to solve the mystery of electromagnetic induction.

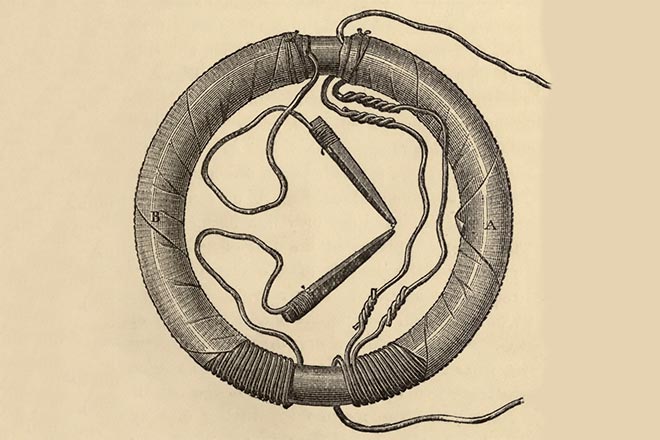

29 August 1831 marked the victory. Faraday’s device consisted of an iron ring and numerous loops of copper wire wound around its two halves. A magnetic needle was put into the circuit of the first half while the second one was connected with a battery supply. When a current was on, a magnetic needle would move to one side and oscillate to another when the current was off. Faraday concluded that a magnet could transform magnetism into electrical energy.

The production of an electromotive force across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field was called the electromagnetic induction. This discovery led to the creation of a current source, an electrical generator and opened the period of wonderful experiments. The physicist described the results of his work in Experimental Researches in Electricity. Thus, he proved the sole nature of electric energy origin, no matter what method was used to elicit it. In 1832, the scientist was awarded the Copley Medal.

Faraday created the first power converter and introduced the term “permittivity”. In 1836, he proved that the charge of a current influenced only the cover of the conductor without any impact on inside objects. Faraday cage is the device created on the basis of this phenomenon.

Works and discoveries

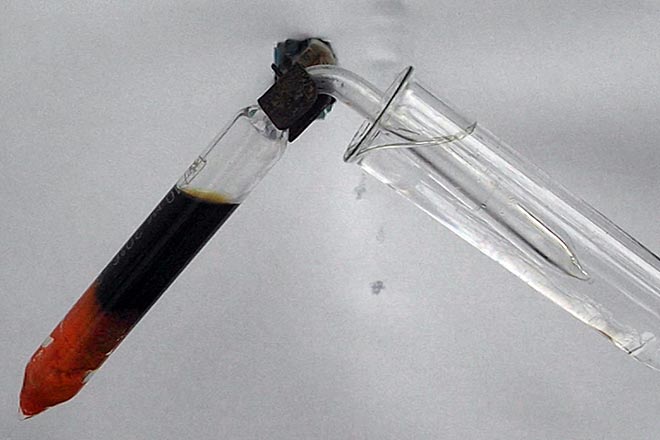

Michael Faraday did not limit himself with physics. In 1824, he discovered benzene and isobutylene. Besides, the scientist came up with the formulas of liquefied chlorine, sulphurated hydrogen, carbon dioxide and ammonia and synthesized hexachlorane.

In 1835, Faraday had to take a two-year break because of a disease; it was probably caused by his experiments with mercury vapor. The professor recovered and came back to work but felt sick again in 1840; he experienced weakness and temporary memory loss. Another recovery period took four years. In 1841, the scientist followed doctors’ recommendations and began to travel across Europe.

The family was close to poverty. According to Faraday’s biographer John Tyndall, Michael’s annual pension was £22. In 1841, Prime Minister William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne signed an executive order and granted him £300 per year under the public pressure.

In 1845, the great scientist grabbed the world’s attention again: he discovered the interaction between light and a magnetic field in a medium (the Faraday effect) and diamagnetism (magnification of substance to the external magnetic field that acts on it).

The English government asked Michael Faraday to solve many technical problems. He created a lighthouse equipage program and methods to prevent ship corrosion; the man also worked as a forensic scientist. Kind and peaceful, Faraday refused to work on the chemical weapon to fight Russia during the Crimean War.

In 1848, Queen Victoria presented the physicist a house in the left bank of the Thames; she paid all expenses and taxes related to the house. Michael and his family moved there when the scientist resigned in 1858.

Personal life

Michael Faraday was married to his friend’s sister, Sarah Barnard. The 20-year-old woman did not accept the scientist’s proposal at once. The modest wedding ceremony took place on June 12, 1821.

The couple’s families belonged to the Protestant community, Sandemanians. Faraday was the deacon of the London community and was chosen as its elder several times.

Death

The scientist was often sick; when the disease disappeared for a while, he worked. In 1862, the man developed the hypothesis about the spectrum line movement in a magnetic field. In 1897, the Dutch physicist Pieter Zeeman proved it and won the Nobel Prize in 1902. He called Michael Faraday the creator of the idea.

Faraday died at his desk on August 25, 1867; he was 75 years old. The researcher was buried next to his wife at the Highgate Cemetery in London. He asked for a modest funeral ceremony, and only relatives were present.

Interesting facts

- The physicist created a series of lectures for children. The Chemical History of a Candle (1961) continues to be published today.

- Faraday’s portrait was printed on a £20 banknote in 1991-1999.

- Rumors had it that Humphry Davy did not answer to Faraday’s request for a job. One day, he lost sight temporarily during a chemical experiment and remembered the persistent young man. Michael worked as a secretary and impressed Davy with his expertise, so that the famous chemist offered him to join the laboratory.

- After the journey across Europe with the Davy family, Faraday was waiting for the position of the assistant at the Royal Institution and worked there as a dishwasher for a while.